Dr. Ken Rietz

October 25, 2023

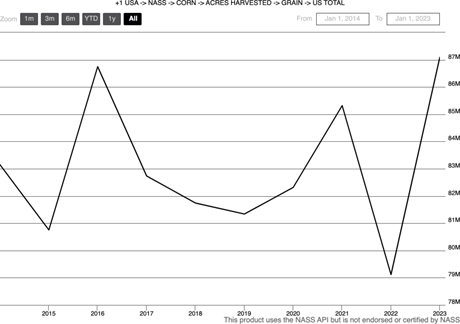

The weather this year in the US was not favorable for corn. The temperatures were often at record highs. Rain was scarce. It was set up for a smaller harvest than even last year. The reality is completely different. This year’s harvest is estimated to be 9.4% larger than last year. The two highest producing years of the past decade for corn crops were 2016 and 2021, each of which had more than 15 billion bushels, the only two years in the past 10 that reached that amount. Although the harvesting isn’t complete for 2023, the USDA estimates that this year will also see more than 15 billion bushels, and possibly fractionally more than 2016 or 2021. Something strange is going on. Let’s investigate why this happened, the implications for the price of corn now, and speculate a bit about the price of corn next year. We start off with a graph of the total harvested amounts of corn for the past several years. Remember that the 2023 value is an estimate.

Figure 1: Acres of corn planted, 2014-2023 (2023 est.)

So, why did this year’s harvest outproduce last year’s, especially given the challenge that weather brought this year? Partly, that is due to our poor memory of the weather this past summer. We remember the high temperatures, and the near drought, but we forget that a band of reasonable rain went through the corn belt near the beginning of summer, at the precise time that it was most needed for the development of corn. Also, the genetic modifications to the seeds enabled the plants to be more resistant to drought. That is how the corn did reasonably well. On top of that, there were more acres planted with corn this year than last, 88.6 million in 2022 and 94.9 million in 2023, an increase of 7.1%, which accounts for most of the difference in harvests. The increased acreage was possibly because the price of corn in 2022 was higher than usual, due to the short supply last year, which encouraged farmers to plant more corn this year.

It should not be a surprise that the price of a bushel of corn dropped significantly this year. Last year, the average price of a bushel of corn was $6.9429; it dropped to $5.8711 this year, down −20.8%. The price bid for a bushel of corn was the lowest since December of 2020. This was caused by the large harvest, while international competition played a role, and China reducing its imports had a big effect. There were two potential factors that did not affect the price. One is the quality of the corn. It would be reasonable to think that the kernels of corn could be somewhat dehydrated this year, lowering the quality of the corn, but that turns out not to be an issue. The percentage of corn that was in excellent or good condition dropped by only 1% from last year to this one. Similarly, a large portion of the corn crop is turned into ethanol to be mixed with gasoline. But the demand for ethanol this past year was nearly constant.

The percentage change in price of a bushel of corn from one year to the next is not well correlated to the percentage change in acreage planted in the next year (a correlation coefficient less than 40% over the last decade). The reduced price of corn increased the amount of corn in silage, and that will also cause the acres planted to drop. The net effect of so many different factors is difficult to predict, but the price will, with reasonable certainty, go up at least some next year.