Dr. Ken Rietz

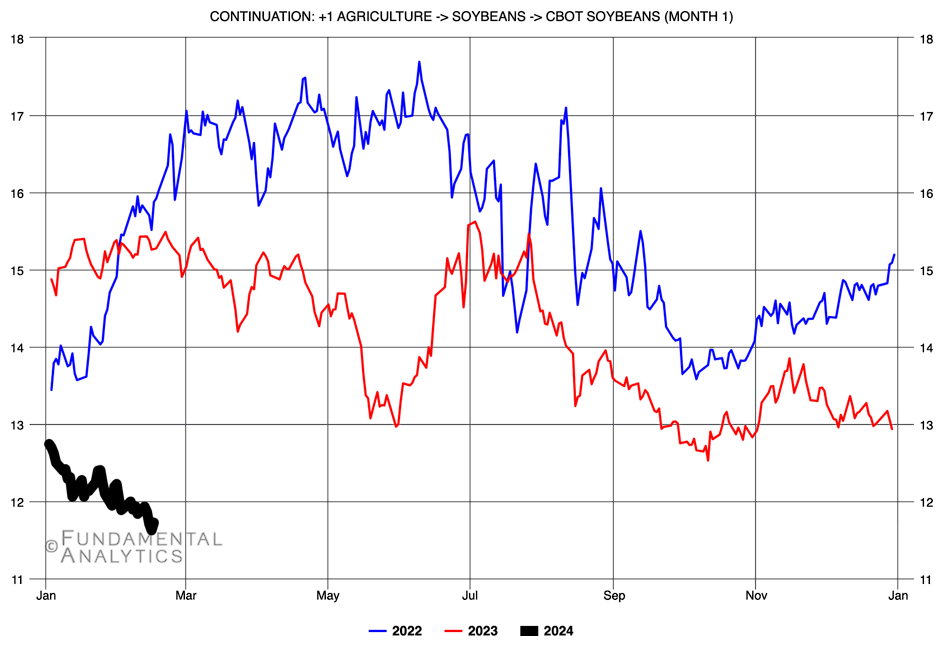

While looking for a topic for this commentary, I ran across an article that surprised me. It raised the question that became my title. The publication was by Morningstar, a subsidiary of Dow Jones, but operating independently. Both corn and soybeans can produce biofuels, with corn making bioethanol for gasoline, and soybeans producing soybean oil that can mix with diesel fuel. I will deal with both here. I will summarize the article, add some background, but then supplement it with some analysis to make the assertions quantitative. First, of course, are the graphs of the prices of front month corn and soybeans futures.

The argument in the Morningstar article is straightforward. The background is that the prices of gasoline and diesel fuel were climbing rapidly in early 2023, so in March of 2023, both branches of the US Congress introduced bills to have the EPA reduce requirements on biofuels to allow more corn-based ethanol and soybean oil to be used to supplement the fossil-based fuels, and consequently lower the prices of the blended gasoline and diesel. This encouraged farmers to plant more corn and soybeans to have the crops to supply the extra demand. The EPA did pass that resolution at the end of April 2023. However, it didn’t work as planned, and farmers ended up with a surplus of corn and soybeans, causing the prices to drop now. Let’s analyze that argument, starting with soybeans, the easier of the two.

The EPA does not specifically restrict the usage of soybean oil in diesel fuel. Straight soybean oil is automatically ultra-low sulfur, so it can be mixed in with ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel, and diesel engines can use it directly. The difficulty was with the price. Pure soybean oil cost more than straight diesel, except during brief periods last summer. Plain economics, and not the EPA, was responsible for the extra soybeans that were not crushed to produce soybean oil. Note that although fewer soybeans were planted in 2023, the amount in storage was near a recent high. The effect was the same.

Corn-based ethanol is a more complicated story. The EPA does control the amount of ethanol that can be mixed into gasoline, and it changes with the season. The regulated specification is RPV, which basically measures how rapidly the fuel evaporates. Adding ethanol increases the value of the RVP of the blended fuel. In the winter, you want higher evaporation so that cars will start more easily, that is, more ethanol. In the summer, you want lower evaporation rates to avoid vapor lock and reduce pollution, that is, less ethanol. The alternate values set by the new regulations on RVP allowed higher levels of ethanol to be used in the summer of 2023, going from 10% ethanol (E10) to 15% (E15). This would have allowed an increase of up to 50% in the amount of ethanol produced from corn. A multitude of factors stacked up against a switch to E15, which was actually cheaper. A few of them were: few gas stations offered E15 gas; even though E15 was cheaper, it also reduced gas mileage so much that E10 provided a lower cost per mile; numerous people posted all over social media that E15 would harm your car’s engine (even more than E10 did). The average amount of ethanol used last summer actually dropped from the summer of 2022, probably due to the reasons cited, higher gasoline prices, and possibly increased use of EVs.

The future of both corn and soybean prices is likely a further decline until we get better information about South American weather conditions and how much acreage is planted in the US. But I still need to answer the question in the title of this commentary. I would say that the EPA might be partially responsible, in the sense that they set up circumstances that led to farmers planting more crops than they would need or use immediately, leading to more crops in storage, and an increase in supply (storage) that lowers the price. But equally Congress probably deserves some of the blame for mandating that the EPA rule that way. There is plenty of room for passing the blame around.