Dr. Ken Rietz

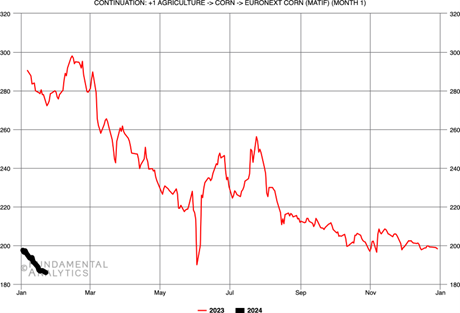

In a previous commentary, I discussed the challenges involved in shipping grain from the Midwest growing regions to New Orleans shipping docks, due to drought conditions on the Mississippi River. As a follow-up on that, the river is now flowing at normal levels, except that the discharge rate into the Gulf of Mexico is down 62%. That is the last vestiges of the drought and reflects the fact that the river takes about a month to drain from Minneapolis to New Orleans. There are, however, two more headaches, both of which are partially man-made and partially natural. The Amazon River is running disastrously low to the extent that almost all shipping has stopped. The other is the rerouting of shipping from the Suez Canal to traveling around the Cape of Good Hope. This involves much more than just increases in time, distance, and cost, as will be seen. First, here is the graph of the cost of Euronext corn futures on the CE exchange.

Note that the futures prices are sinking, not spiking. That is because the market does not expect these obstacles to affect prices by the time the next harvest is ready to ship. It is worth watching, though.

Brazil has a lot of arable land and has the potential to increase production significantly. Or so goes the narrative. Agribusiness is the biggest factor in deforestation, the leading cause of the Amazon River drought. (El Niño and climate change are the other two main causes.) The Amazon River is drying up to the extent that native villagers in some places are digging wells in the river bed in order to get water. Shipping in many places upstream is reduced to using dugout canoes and balsa rafts; larger boats are stuck on the ground when loaded up. The estimate of scientists is that it will take two full years of normal amounts of precipitation for the Amazon River to recover. And with the current deforestation, normal precipitation is not likely to occur soon. This issue was addressed at COP28, with plans to restore 60,000 square kilometers of degraded land to rainforest by 2030, at a cost of US$204 million. Additionally, Brazil has passed a law that at least 80% of newly-acquired Amazon land must be maintained as native rainforest, and at least 35% of already-owned Amazon land must be returned to rainforest. The drought hardly affects shipping alone. Growing crops is becoming a challenge as well.

The newest hazard to global shipping is the attacks on ships through the Red Sea to get to the Suez Canal, despite the pledge of protection from the US and other countries. That means the ships will travel around the Cape of Good Hope. Several large companies have determined to do that, at least for the time being: MSC, Hapag-Lloyd, CMA CGM, and Maersk Line. The total traffic going through the Suez Canal normally is about one sixth of all global trade. Sailing around Africa is not a decision to be made lightly. The obvious problems of the extra time and cost need to be factored in, but there are other, less obvious factors to be considered. Sailing around the Cape of Good Hope is treacherous. Bartholomew Diaz, the discoverer of the cape, originally called it the Cape of Storms. More than 1000 ships have sunk there, which is the source of the local nickname Graveyard of Ships. Of course, modern ships are much safer than 100 years ago, but the trip will be unpleasant, and more fuel-intensive, not to be ignored. The World Bank ranked the major South African ports among the worst performing in the world, and the extra distance means that many more ships than usual will need to to stop there for at least fuel. Maersk Line is considering using other countries’ ports. Bunkering—pumping fuel between ships—is becoming more common.

Both of these issues will affect global prices of just about everything that is imported. But both of them are fairly recent, and the market is not sure how to incorporate the effects. But it is safe to expect that these problems will push prices higher, all other things being equal.